Reading and COVID-19: What the Data Show and What Lies Ahead

In spring 2020, it felt like everything was changing, and changing quickly. The COVID-19 pandemic brought uncertainty and disruptions to the lifestyles most of us had never experienced. Among the dramatic actions taken to ameliorate the spread of the virus, schools closed, and most remained closed for months or longer.

Growing up in Wisconsin, days off from school because of the cold or snow were normal, but extended, global school closures were unheard of. UNESCO estimates school closures brought about by the pandemic were the largest disruptions to education in human history

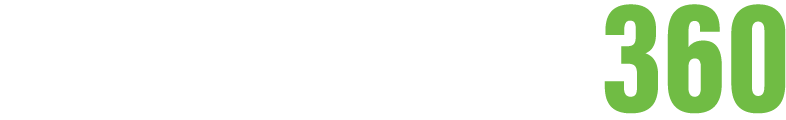

When schools closed in 2020, Acadience® Learning became keenly interested in what the data would show in terms of the progress students were making. Data from spring 2020 was basically nonexistent, so we had to wait until fall 2020 to examine data and compare student performance to pre-pandemic levels. What we saw was disheartening, to say the least. This is what the Acadience Reading Composite Scores look like for the last fall of the pre-COVID era, alongside fall 2020 for each grade:

What We Learned

The largest discrepancies were seen in earlier grades (except for kindergarten), with first grade showing the biggest pandemic-era losses. This trend may be for several reasons. First, earlier grades had a larger proportion of their overall education disrupted. For first grades in fall 2020, missing spring instruction meant missing a quarter to a third of overall schooling. Whereas for a sixth-grader, that same disruption would have been less than 10 percent of their overall time in school (i.e., since kindergarten).

Another potential explanation is that literacy assessment in earlier grades may focus more on skills influenced by in-person instruction. Skills such as knowledge of letter names and phonemic awareness may require more explicit, teacher-led instruction than skills such as building fluency with connected text. At later grades, most students have the essential prerequisite skills to read on their own and may have experienced less impact being out of the classroom.

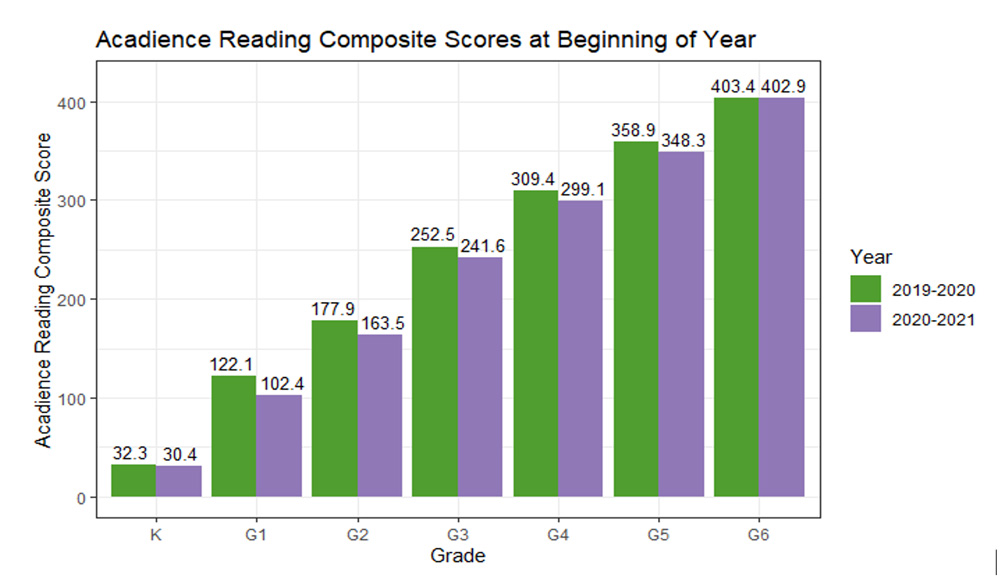

One piece of evidence in favor of more foundational skills being especially impacted by the pandemic is shown in the Audience Reading subtests, which demonstrated the biggest drop in scores. The year-to-year decline in scores was the largest for First Grade Phoneme Segmentation Fluency (PSF), an indicator of phonemic awareness. The graph below shows the distribution of scores for this measure at the beginning of Grade 1; it is apparent fewer students were scoring high on PSF. Since phonemic awareness is such a foundational skill for reading, this suggests more foundation skills were especially affected.

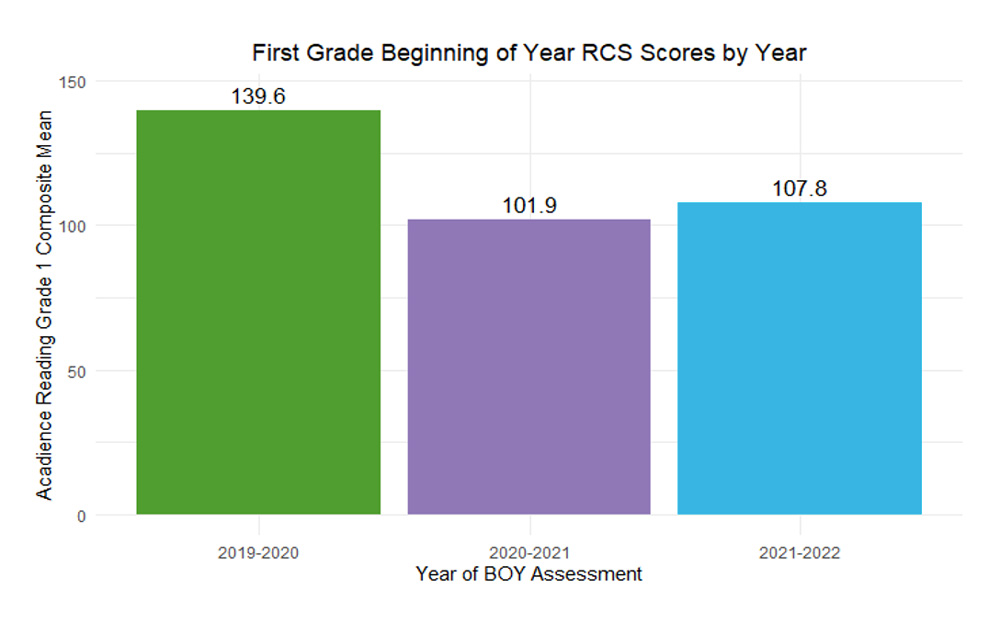

In case this has been too depressing so far, bear with me: There has been some improvement during the fall 2021-2022 school year. If we compare the grade that showed the largest drop, first grade, from 2019, 2020, and the most recent fall 2021, we can see scores that are still well below pre-pandemic levels, but have demonstrated some rebound from 2020.

What have we learned?

First, reading skills have suffered since the beginning of the pandemic. This impact has been especially pronounced in earlier grades, with the largest gaps being observed in first grade. Some skills have been more impacted than others, with PSF showing the biggest drop. However, we have seen some evidence that reading skills have improved a bit from the lowest point of the 2020-2021 school year.

So, having established that students’ reading skills have suffered, what can be done? We have already seen early evidence that students are beginning to recover, but it’s understandable that educators won’t simply want to wait around and hope the trend continues.

There are some “toolbox” approaches you can use to help bring students’ reading skills back to pre-pandemic levels:

- Identify and intervene early. With the observed gap in reading skills, early identification and intensive intervention is more important than ever. Not only are gaps larger for early grades, but intensive intervention is also more effective for first grade and kindergarten. The earlier students with reading difficulties are identified, the easier we can flip the narrative and help them reach reading levels that exceed pre-pandemic levels.

- Align goals with the ODM. The Outcomes Driven Model, or ODM, forms the backbone of Acadience Reading. The ODM follows a process of identifying students in need of support, planning support, evaluating the support, and reviewing the outcomes for each student. With widespread losses in reading skills, it is not practical to intervene intensively for each student, but the ODM may lead merely to a less resource-intensive bolstering of Tier 1 support.

- Maintain data collection. Not every student will be identified early enough for intensive intervention to make its full impact (though it never totally loses its effectiveness). For students in all grades, closely monitoring progress is critical. Progress monitoring helps identify students for whom reading interventions are proven effective, and those who need a different strategy. Educators and school psychologists should work to maintain the schedule of benchmark assessment and progress monitoring as much as possible.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a shock to everyone and upended all of our lives. Educators and students felt this shock acutely, and the flexibility demonstrated by teachers and students alike is admirable. The global disruption to education did severely impact reading skills, but we are beginning to see some recovery, at least in Acadience Reading Scores.

While there is still work to do, persistence and attention are proving to be the keys to getting reading skills back on track.

Register for the webinar, Reading Intervention in Middle School: Critical Steps for Success, here